A Century in Motion – Part 5: The Automobile and Dadaism, the Definitive Break with the Past

28 February 2025 2 min read 4 images

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi, Taschen

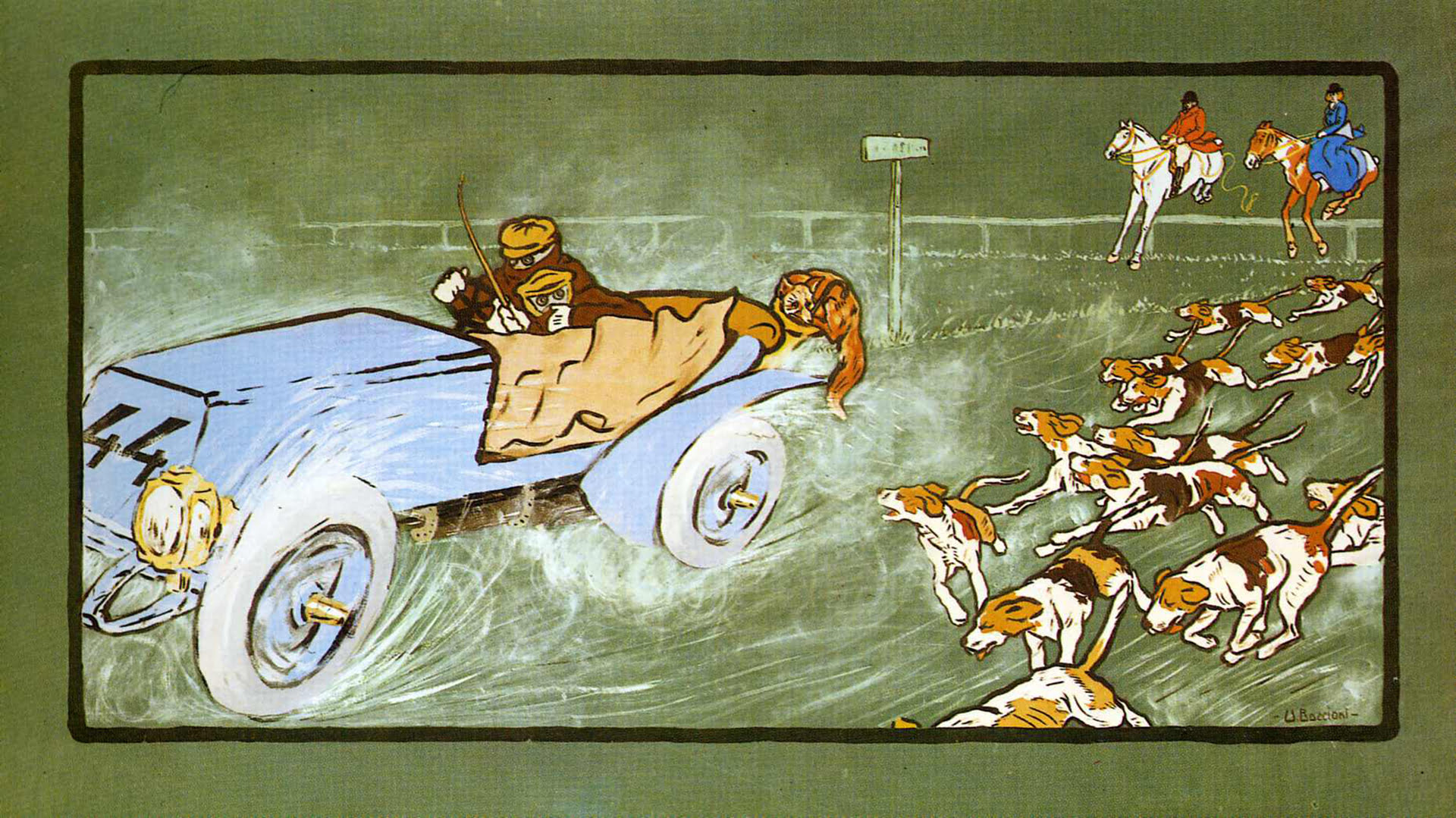

Sometimes extremes do meet: if the aristocratic elegance of Deco had marked an entire era, already during the War — in 1916, in Zurich — an artistic and cultural movement had been born whose very soul resided in extravagance and in a total disregard for everything that was homologated, standardised, tamed. Its name was Dada, and from the immediate postwar years onward it inspired cinema, literature, and the arts, graphic design above all.

To give some measure of its disruptive force, it is enough to recall that art — thanks to Marcel Duchamp — went beyond all rules, legitimising the concept of "ready-made." Duchamp's provocation rested on the assumption that any ordinary existing object can be seen as art: even a porcelain urinal, signed and dated. What more violent severing of the mannered rules of the past could one imagine?

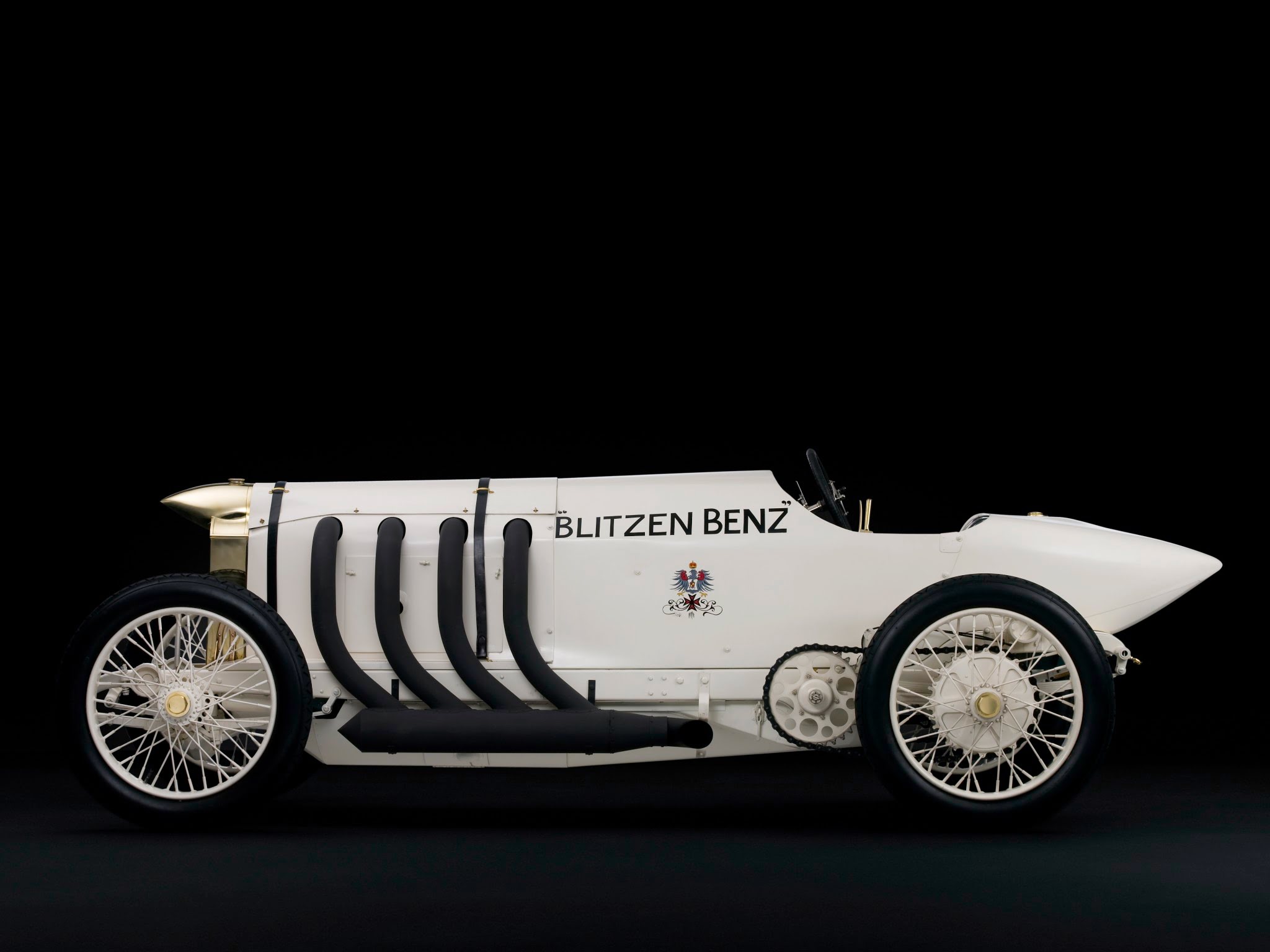

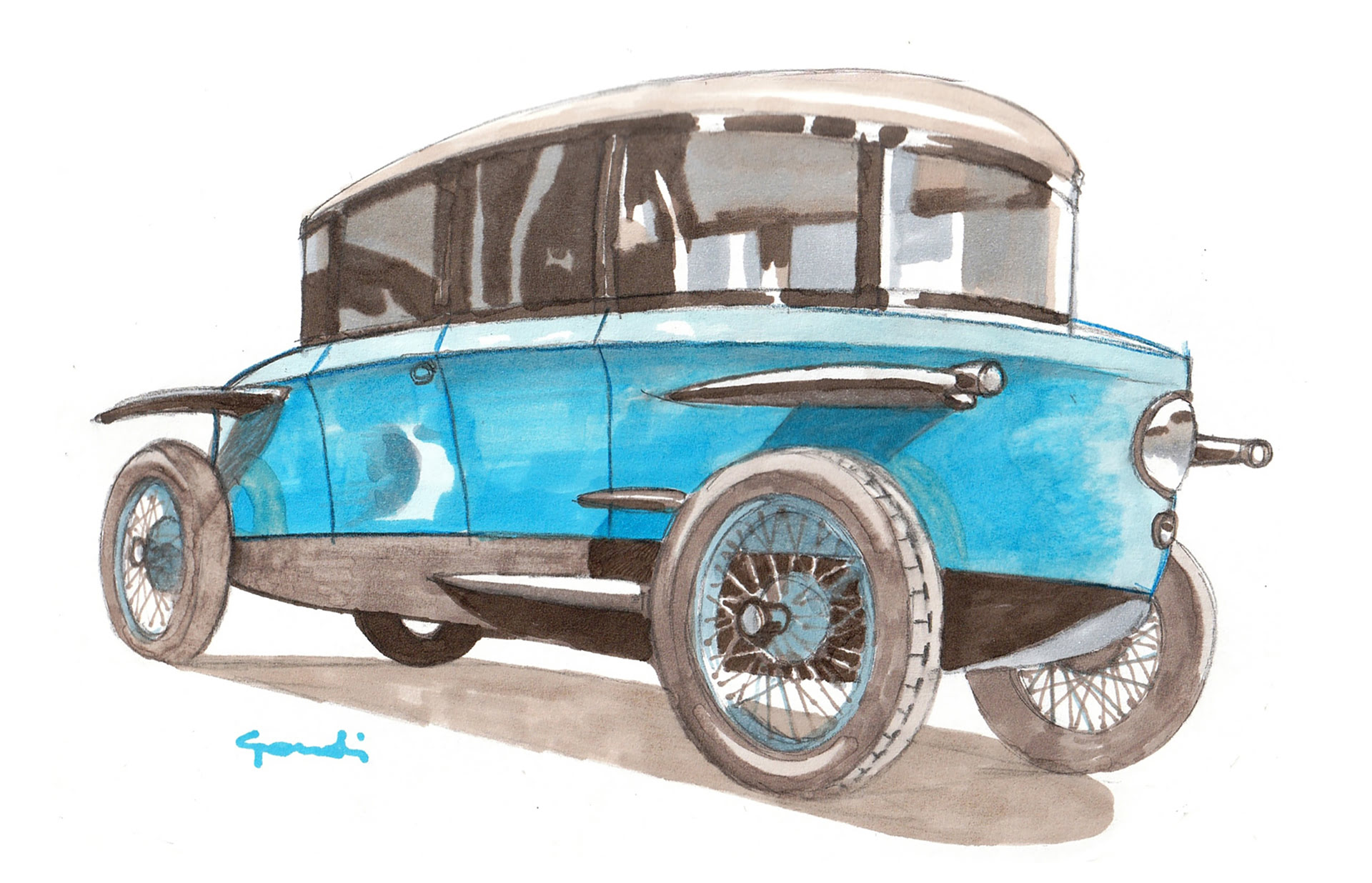

Cinema, too, became a showcase for innovation, carrying the automobile into a distant future: in Fritz Lang's famous film Metropolis, the extraordinary Tropfenwagen of Edmund Rumpler make their appearance — cars that anticipated the necessity of a style attentive to aerodynamics, so neglected at the time, and to functional habitability. The few Tropfenwagen that were actually produced — a premonition of the minivans of the 1980s that no one ever bought — were destroyed in the film's most staggering scene. What a shame.

The film also prefigured, through architectures of astonishing contemporaneity, the world we live in today.

Hollywood — its directors, its stars — began to spread across the world the image of America, a way of life in which the automobile held a central and defining place. Perfect for a world hovering between reality and dream, the Ruxton Model C, with its extravagant horizontal striped paintwork fading into white, marked a deep cultural difference.