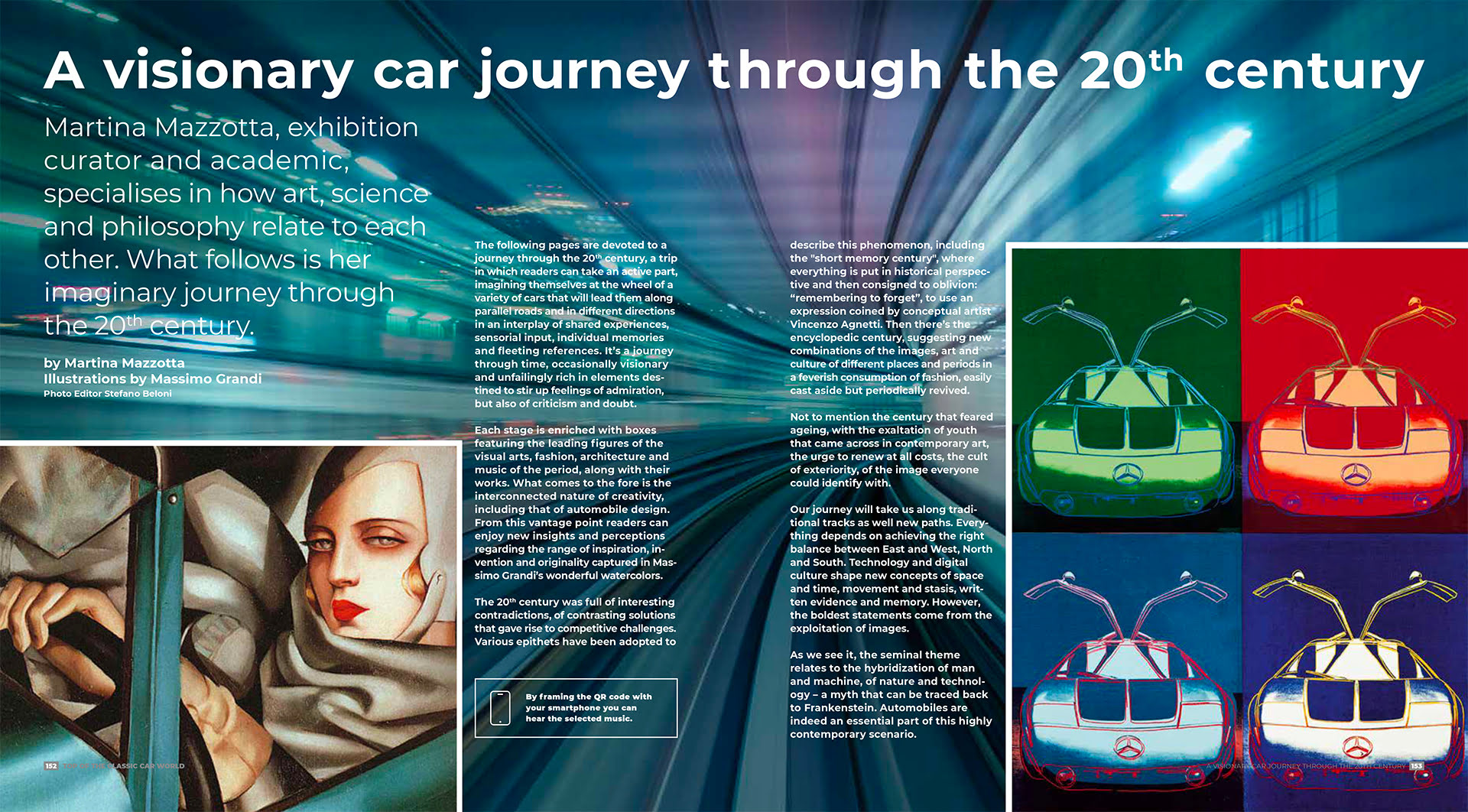

A Century in Motion - Part 2: Futurism and the Myth of Speed

07 February 2026 1 min read 3 images

Photo credit: Mercedes-Benz, Wikipedia

Let us try, for a moment, to return to a world brought to life by the invention of the railway and by urban growth driven by industrialisation. A world, at the end of the 19th century, in which just one magical element was still missing: the ability to move independently, using one’s own vehicle. Strange, horse-less machines began to appear - closer to carriages than to what would soon be called the automobile.

Progress found its stage in the World Expositions, and the Paris Exposition of 1900 marked a true turning point, showcasing what the future would become. Speed was now ready to turn into the symbol of a new way of living: the Futurist movement embraced it as an ideal, and the pursuit of ever-higher speeds began on both sides of the Atlantic.

Engines grew more powerful: from the internal combustion engine made commercially viable by Karl Benz, to early experiments with electric propulsion, performance continued to rise. In 1899, Camille Jenatzy’s La Jamais Contente - an electric car - exceeded 100 km/h. Tastes changed as well: women adopted more practical clothing and wide-brimmed hats, gradually asserting their independence. The chauffeur-driven automobile would represent the first major step in this direction.

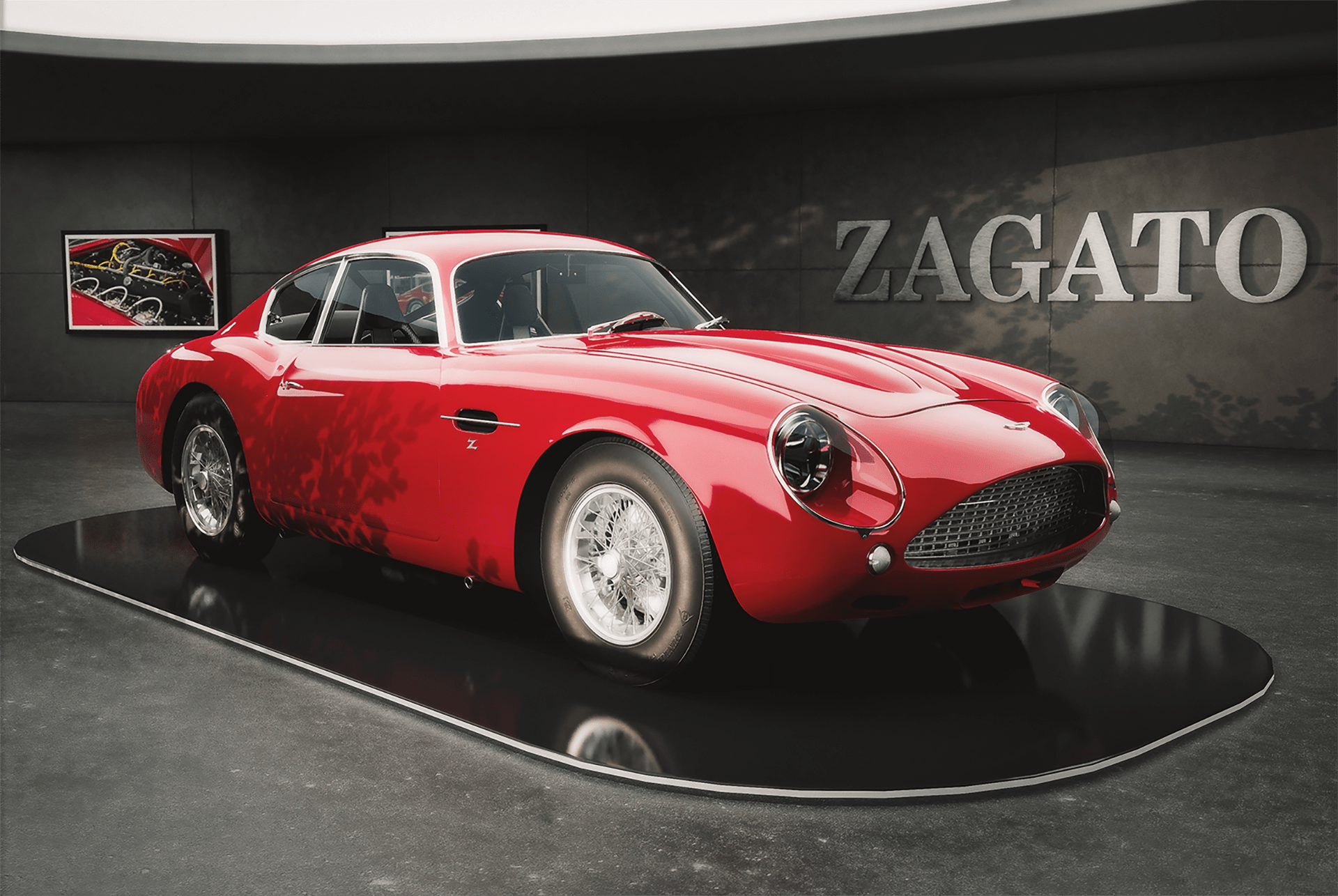

Architecture, too, felt the need to move beyond the Belle Époque and its Art Nouveau language, searching for new expressions in the geometric forms of Mackintosh or the urban creativity of Gaudí. The automobile, increasingly widespread - albeit still confined to the wealthier segments of society (Enzo Ferrari’s father, a small entrepreneur from Modena, already owned a modest De Dion-Bouton) - demanded significant changes to urban planning, and cities began to transform accordingly.

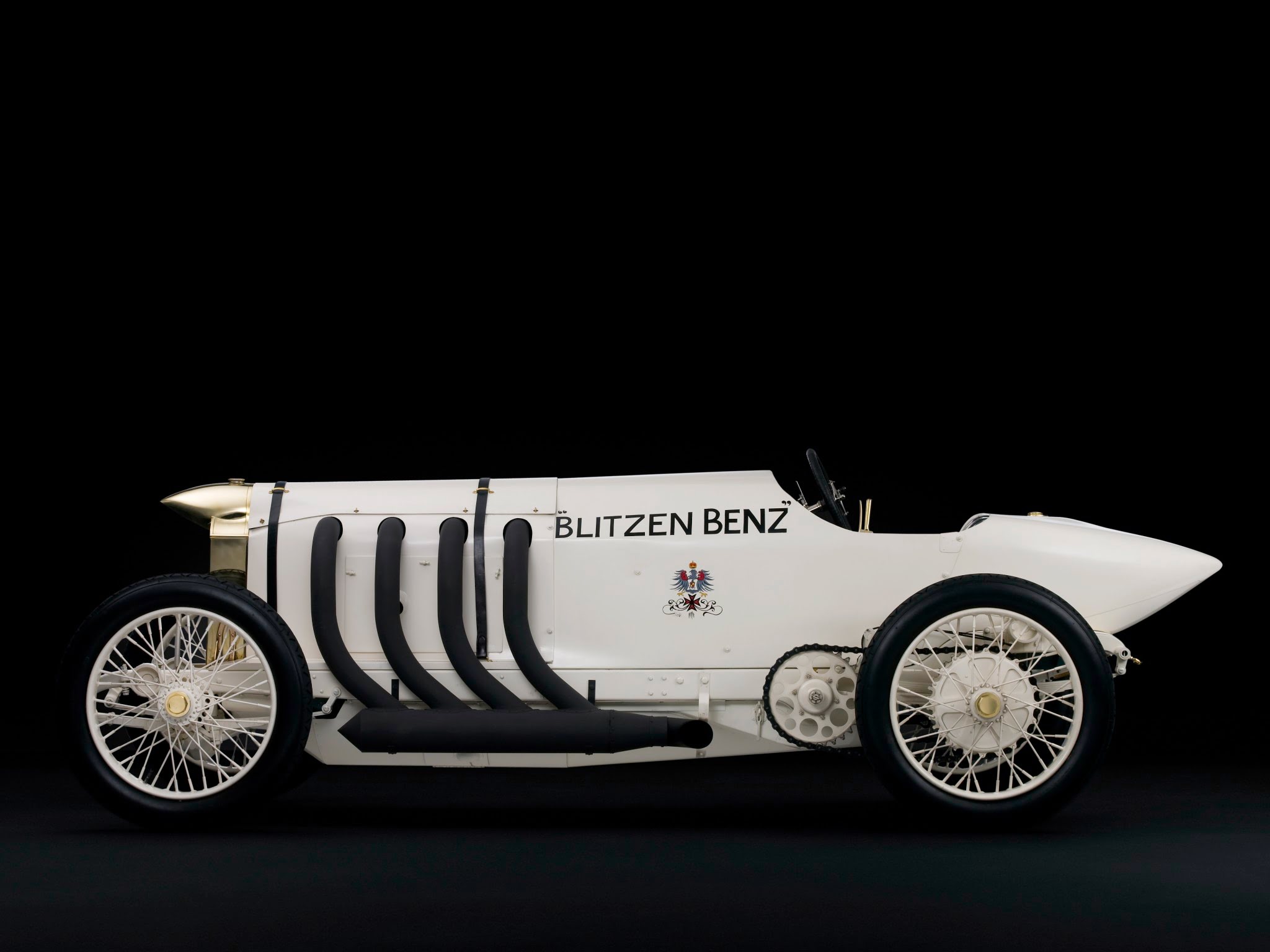

Motor racing became a powerful laboratory for technical progress. The rivalry between manufacturers - then competitors - Daimler and Benz led, by the end of the decade, to cars achieving previously unimaginable speeds. In 1909, the Blitzen Benz (“Lightning” in German) exceeded 200 km/h at Brooklands.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the automobile became a reality for everyone thanks to Henry Ford’s introduction of the assembly line. The Model T marked the beginning of a fundamentally different automotive culture between the USA and Europe - a divergence that still exists today.