A Century in Motion – Part 4: How the Elegant Rigour of Art Deco helps the World forget a Cruel War

21 February 2025 2 min read 4 images

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi, Michael Furman, Palazzo Reale Milano, Pexels

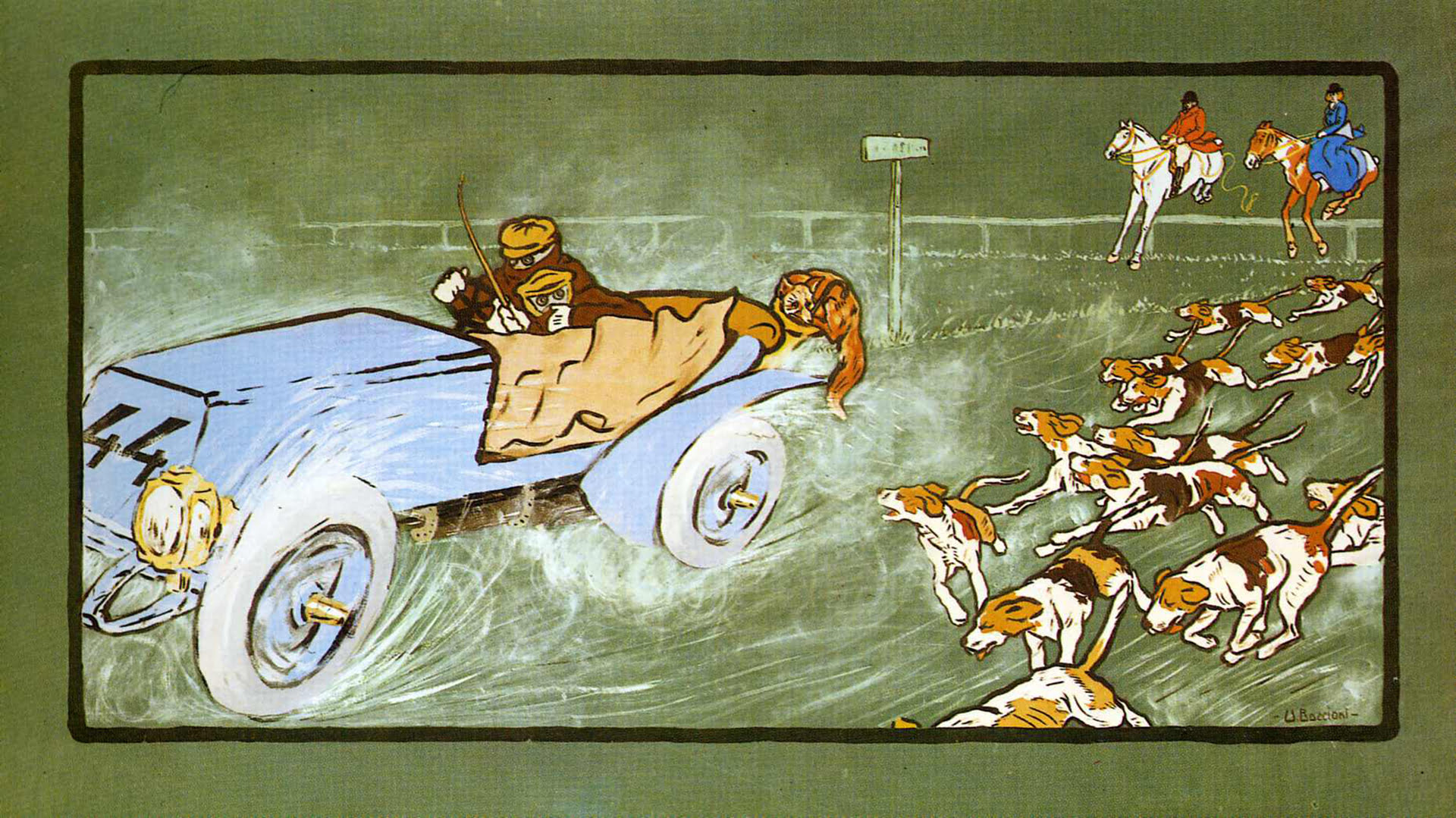

In just twenty years, the world had changed. The automobile, the aeroplane, agricultural mechanisation and Henry Ford’s assembly lines had replaced horses, hot-air balloons, the ox-drawn plough and craft-based industry. Art, having moved from nineteenth-century figurative traditions to Futurism, had shattered centuries-old conventions.

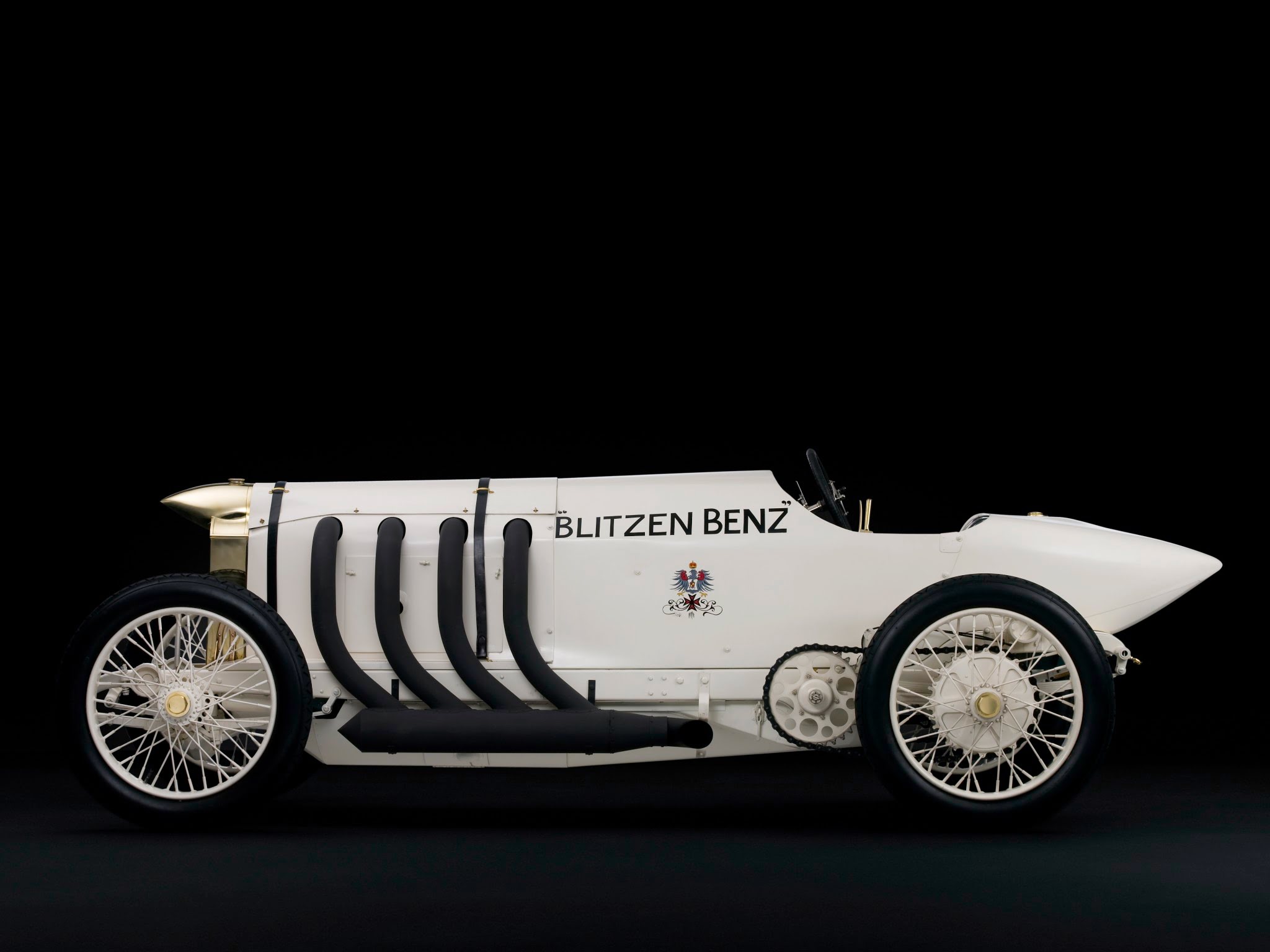

Yet all of this, between 1895 and 1914, had not been enough. The First World War, among its immense and tragic consequences, also became a powerful technological stimulus for the mobility industry — whether in aviation, automobiles, transport vehicles of every kind or ships.

It was the end of the conflict that effectively ushered in the 1920s, when newly regained peace sought, in an effort to forget, wellbeing and ever more extreme luxury. Architecture, fashion and the decorative and visual arts expressed themselves through a language of perceived unity. A model was created to define the new world.

This was true in architecture, where buildings and furnishings adhered to the same design principles, and in fashion, where clothing, jewellery and accessories followed elegant rules of formal rigour.

Naturally, the increasingly desirable automobile adapted accordingly. One need only look at the Bugatti Type 35, which introduced the classic, rigorously shaped radiator reminiscent of a horseshoe — perfectly aligned with the best Deco taste. Art Deco’s inspiration from the animal world was not limited to cars: alongside serpent-shaped horns on increasingly spectacular vehicles, jewellery echoed the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosopher much admired by the younger generation.

Ettore Bugatti became, for the automobile, the true symbol of the era. For him — an Italian who settled in Alsace, in Molsheim (the famous radiator was in fact inspired by the arch of the town hall in that very city) — everything had to be perfect. Already in the 1920s, at racing events, he erected majestic tents for drivers and guests, complete even with showers.

Bugatti, son of master cabinetmakers and brother of the sculptor Rembrandt Bugatti, possessed a deep sensitivity to beauty.

Yet his ultimate goal was victory. The desire to see his cars triumph — combined with inspiration drawn from the world around him — led Ettore to create what could be considered the first truly modern-looking racing car: the Type 32 “Tank”. Riveted like the armoured vehicles of the time, it was extremely fast but suffered from unstable road holding, due to the limited understanding of aerodynamics in those early years.

The years leading up to 1930 were magnificent — years with much more still to tell. We shall discover the rest next week.