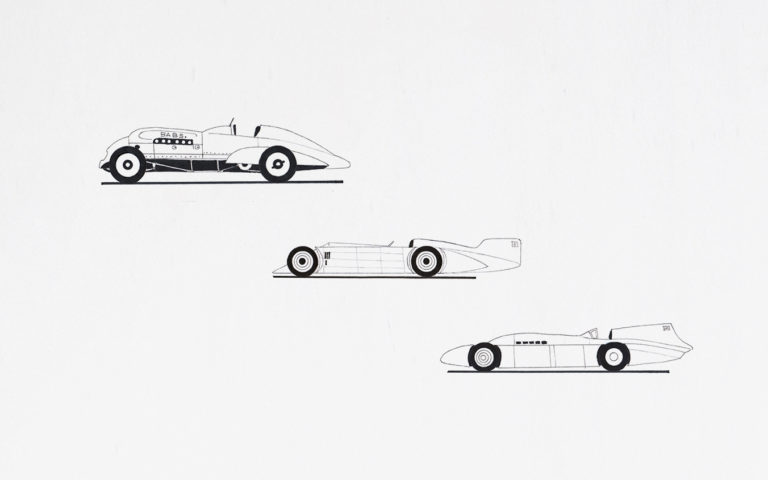

The Speed Record Story 5 - Aircraft engines for new milestones

02 May 2021 4 min read 8 images

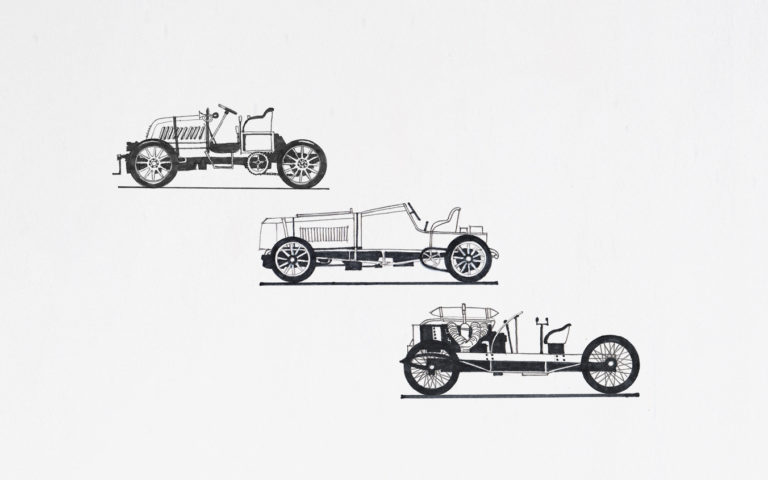

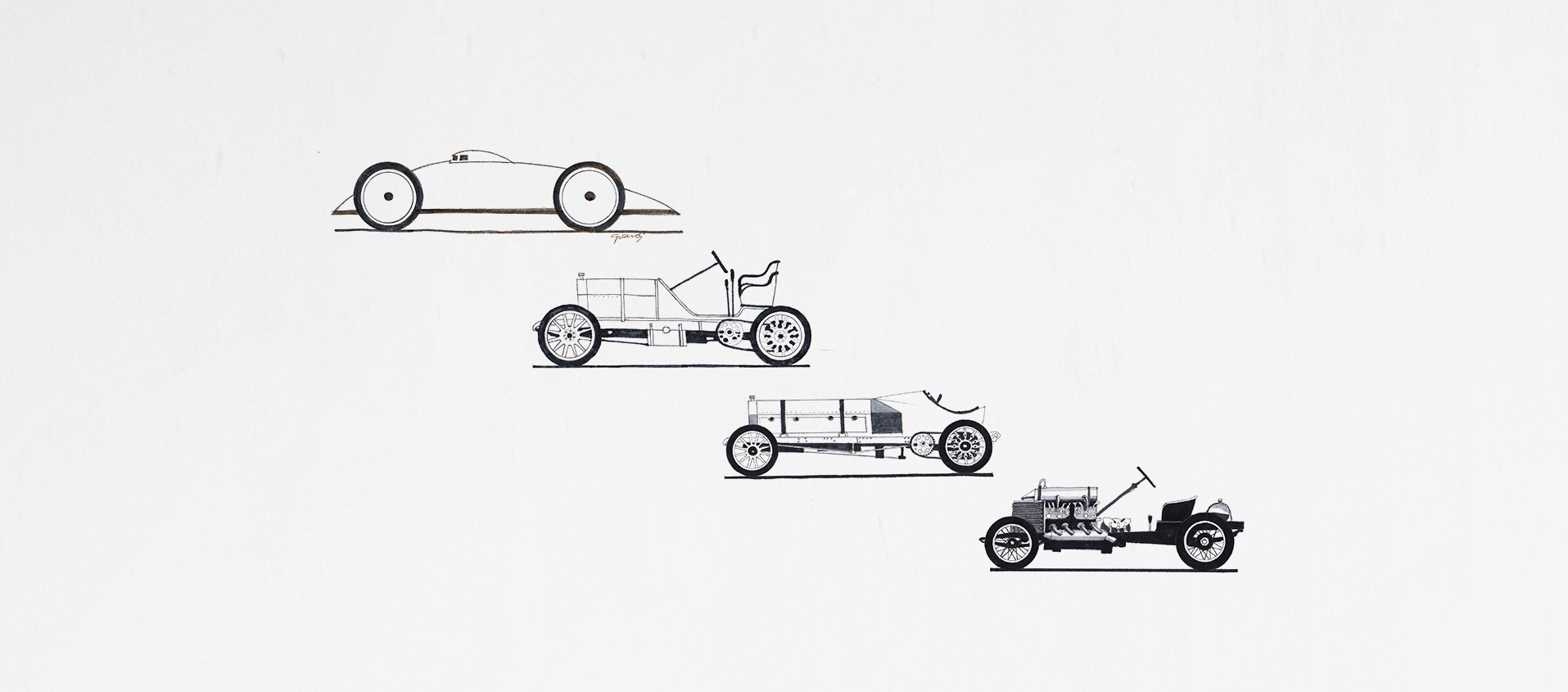

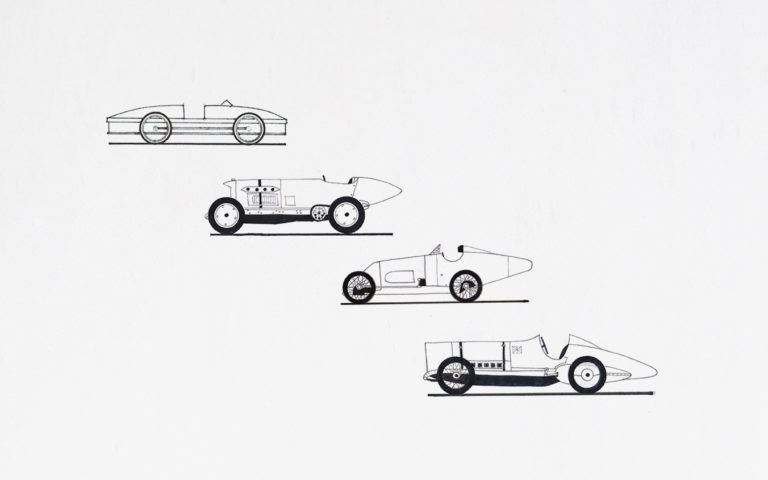

As the land speed records continued to rise, it started to become clear that using modified production vehicles was no longer enough. Indeed, the 235 km/h reached by Campbell’s first Bluebird was easily beatable, and the record holder himself was already busy building a new Bluebird. The year was 1925 and many people wanted to write their name in what was rapidly becoming a veritable ranking of courage.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In