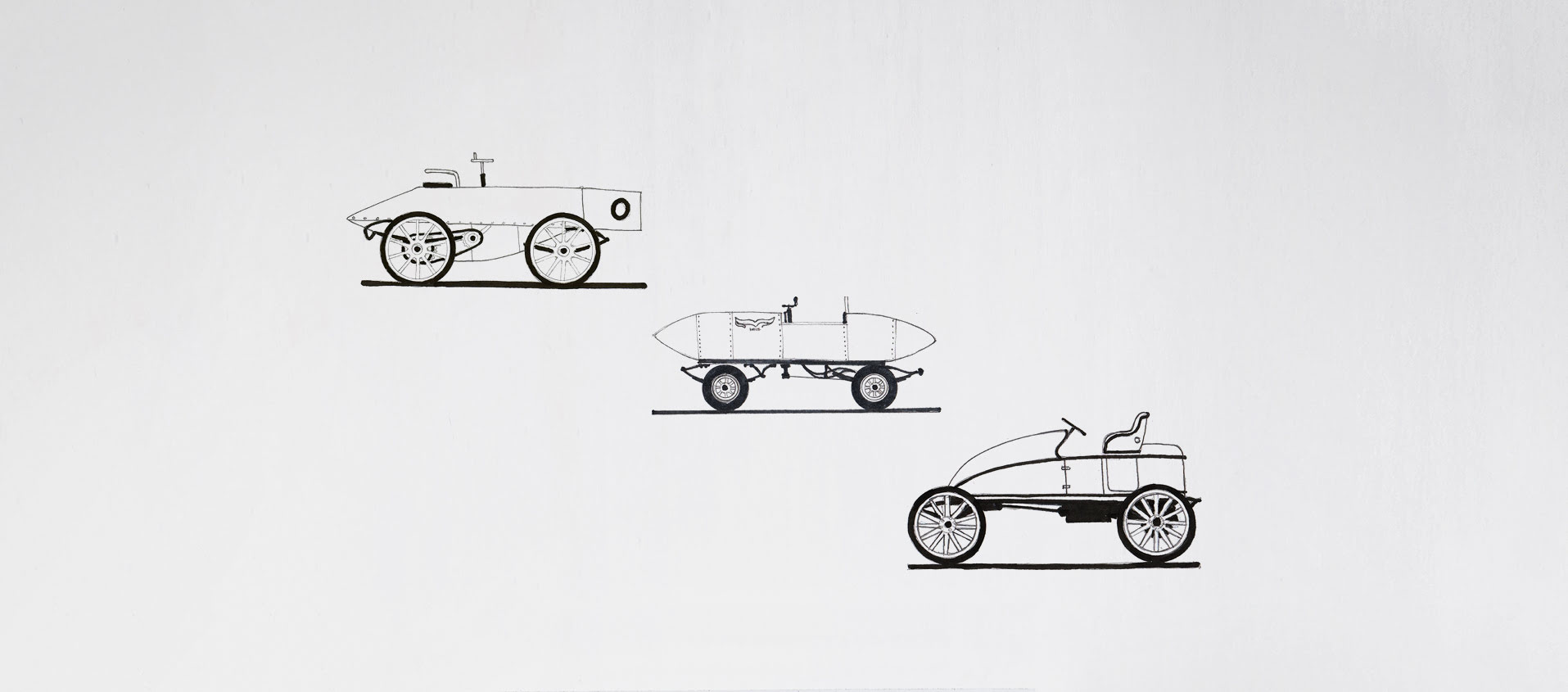

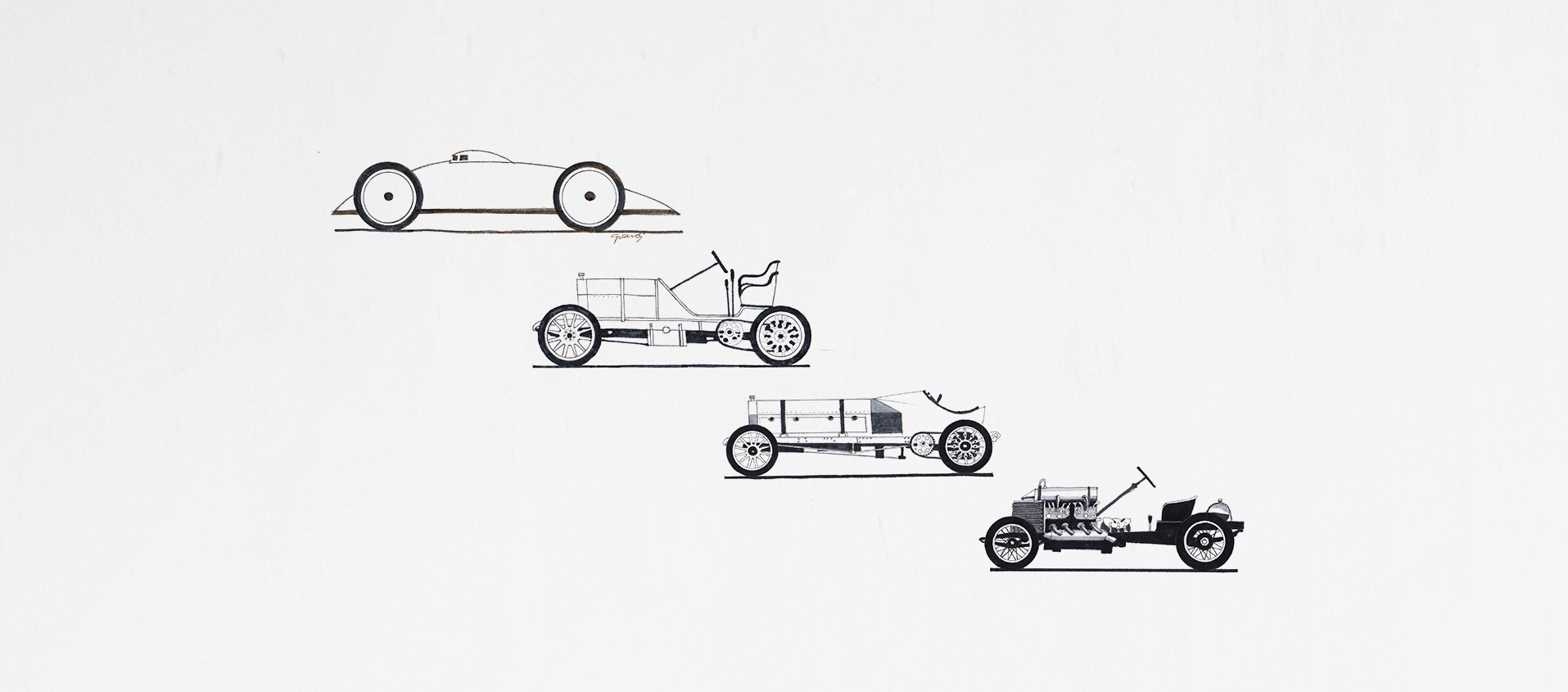

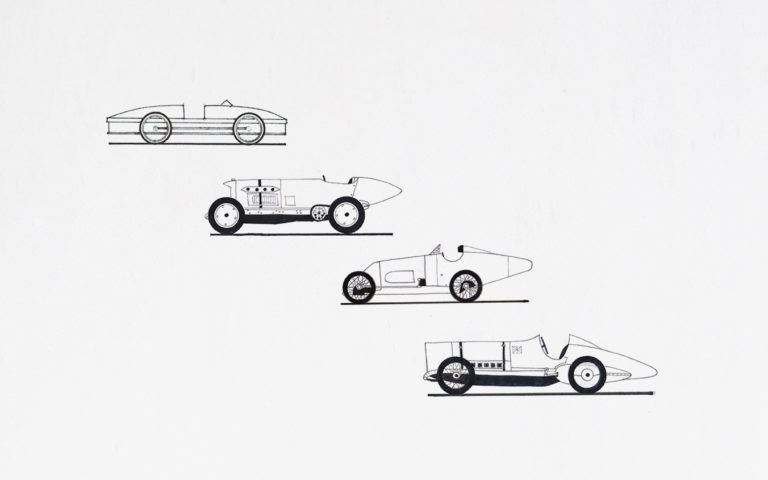

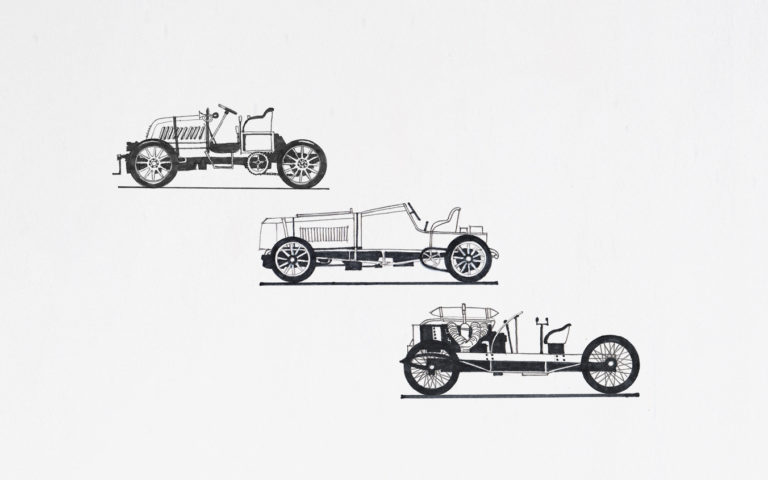

The Speed Record Story 2 - The race to 150. In a world full of innovations, Henry Ford himself broke the world record

11 April 2021 3 min read 8 images

To truly get into the spirit of this story about man’s desire to set newer and faster speed records, you have to imagine yourself in a world that seems so distant because of the technological progress we’ve made over the last 150 years. Life in previous centuries suffered minimal changes: horses were everyone’s means of transport, oxen pulled ploughs, mills, powered by the wind or water, produced energy. Generation after generation.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In