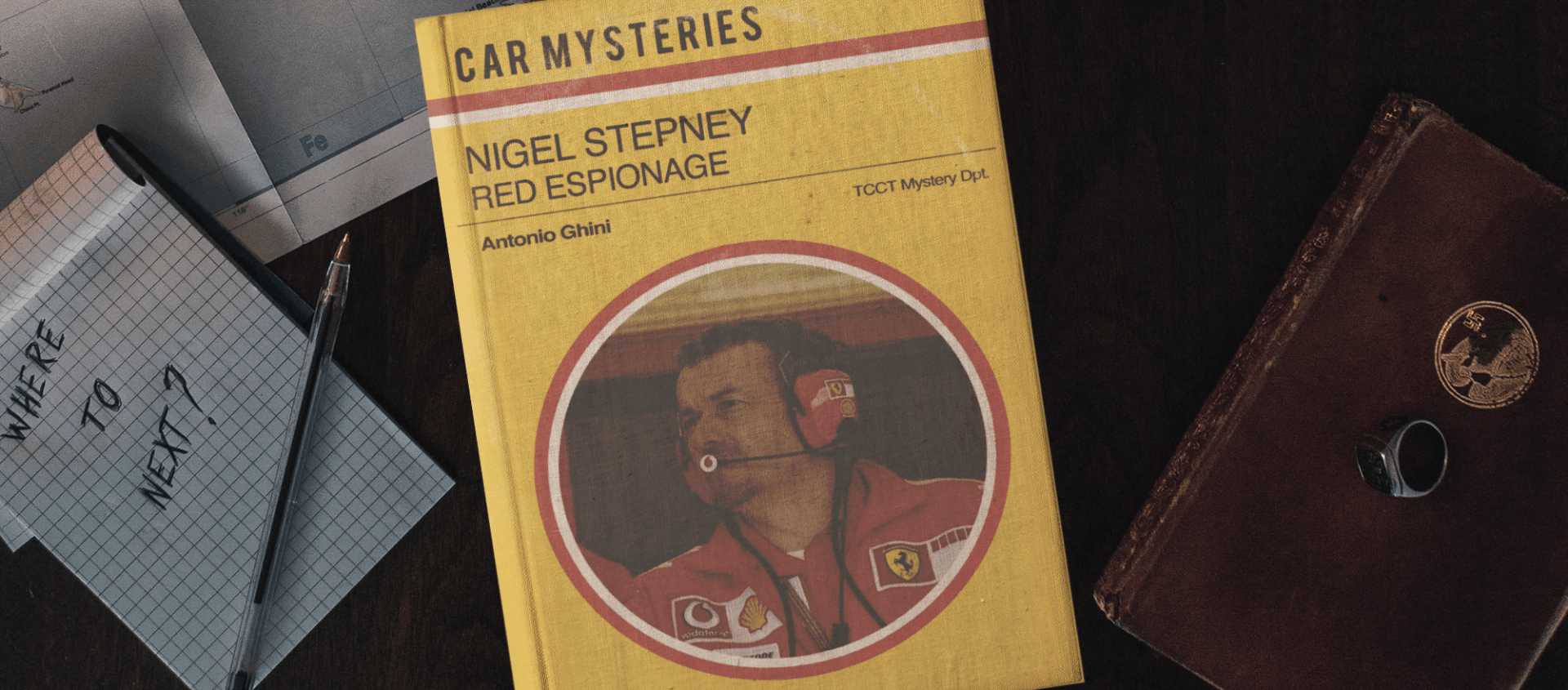

Red espionage

05 May 2020 2 min read 3 images

The tension in Maranello was palpable. Luca di Montezemolo, the heart and soul of the company, was furious. At that point, no-one knew why. There were repeated meetings with Todt, Domenicali and Almondo but no-one in the company had a clear idea of what was happening. In reality, people knew that something serious had happened within the Sports Management area, the department dedicated to Formula 1.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In