Unforgettable Car Geniuses: Paul Jaray

22 February 2025 5 min read 4 images

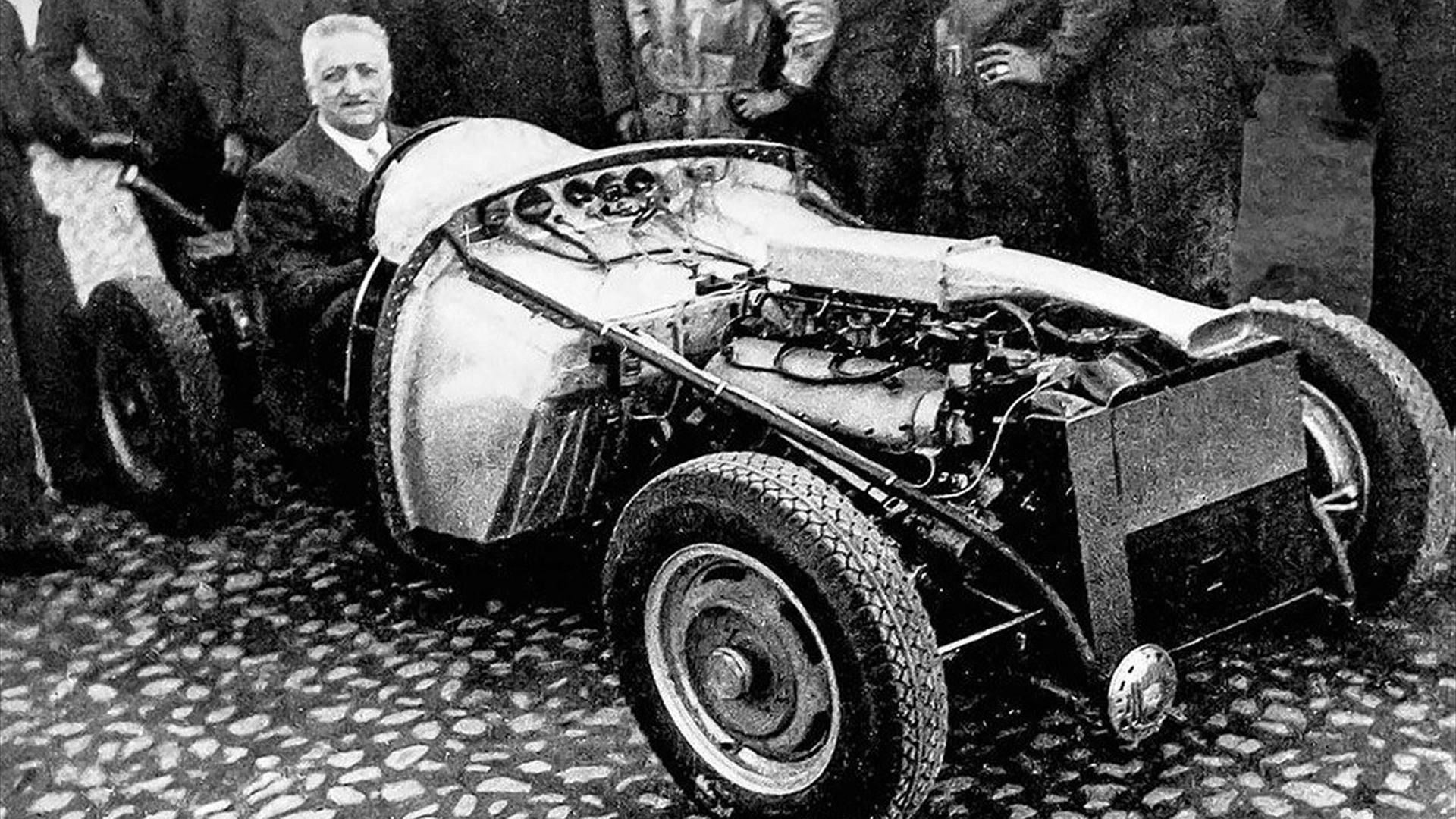

Photo credit: Audi, Massimo Grandi, Wheelsage

From February 20, we enter the sign of Pisces, and here is an unforgettable genius of that zodiac sign: the wizard of aerodynamics, Paul Jaray, an Austrian from Vienna born in 1889. As a young man, he wrote poetry, drew, and composed music. He became an engineer, following the avant-garde spirit of the time, which promoted a universalism where arts and sciences should unite in the name of progress.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In