Unforgettable Car Geniuses: Ferruccio Lamborghini

03 May 2025 4 min read 4 images

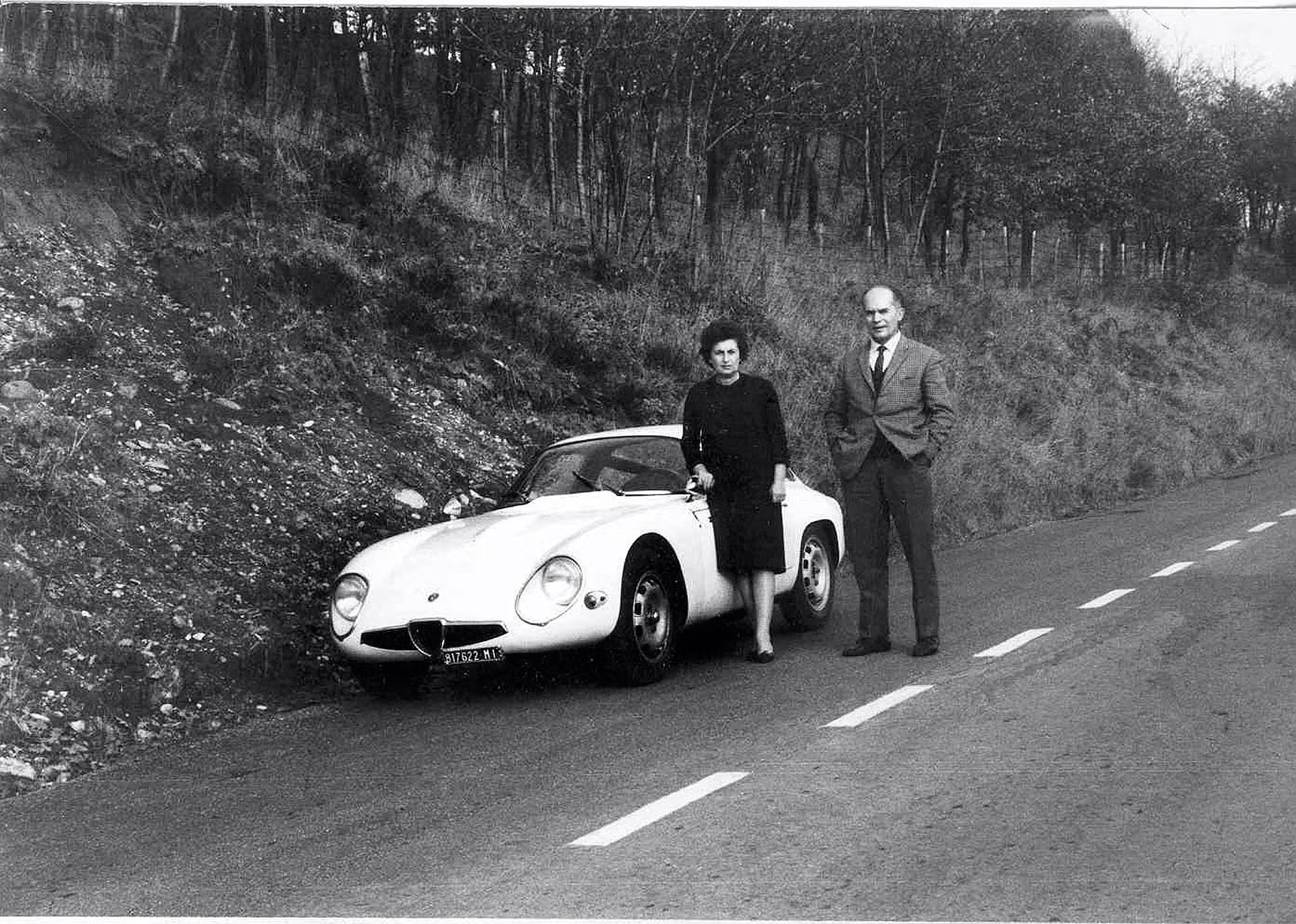

Photo credit: Lamborghini, Museo Ferruccio Lamborghini

Each of us is born with a calling that often reveals itself in the earliest years of life. Ferruccio Lamborghini felt his passion for engines immediately, leaving his hometown Cento, near Bologna, to work as a mechanic in the regional capital. His first motorcycle, engine work, a natural talent for mechanics, and his studies set the foundation. When Ferruccio was 24, Italy entered the war, and he was drafted: it was 1940, and his technical knowledge led to his assignment at the Italian outpost on the island of Rhodes in the Aegean Sea, where he became responsible for vehicle maintenance. Among his traits: charm and audacity. We need to know this—and it’s why this story, a bit outside Roarington’s usual tone, is essential to understand this unique character.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In