GT 40, Born out of spite

07 October 2023 3 min read 5 images

Photo credit: Ford, Wheelsage

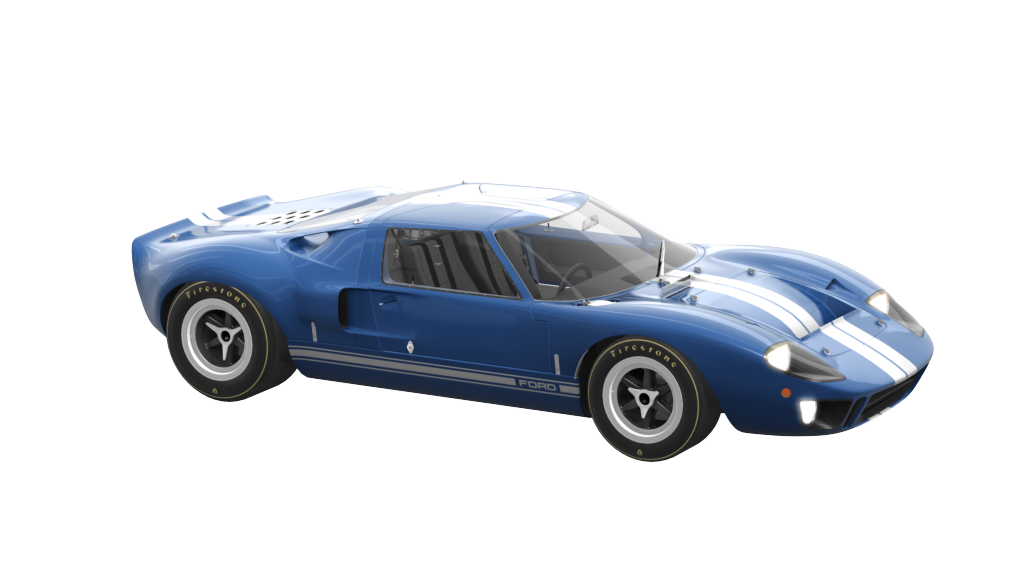

In 1963, Henry Ford II took Enzo Ferrari’s refusal to sell his Maranello company so personally that he decided to create his very own racing department to build a car that would outperform Ferrari at Le Mans. That car was the GT40, a masterpiece deserving of its own tale. It has become so iconic and ingeniously designed that even in its modern reimagined form, it remains highly captivating. The GT40 occupies a special place in automotive history.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In