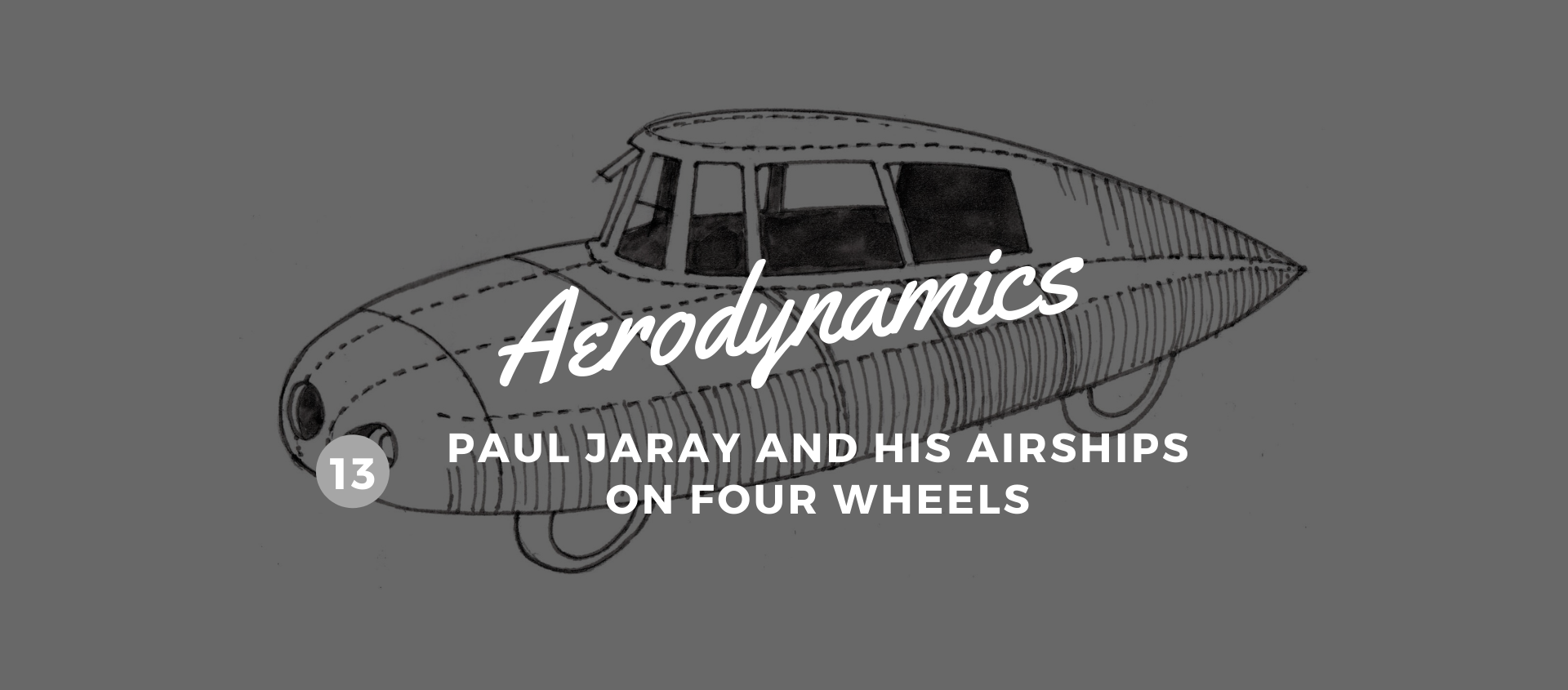

1921. Paul Jaray and his airships on four wheels

04 May 2020 2 min read 3 images

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles, on 28 June 1919, formally ended the First World War and, with it, Germany’s activity in the field of aviation. This left Paul Jaray, a young engineer who had worked in the Zeppelin wind tunnel on the streamlining of German airships, suddenly wondering what to do with his expertise. Until he decided to apply it to the motor car.

Register to unlock this article

Signing up is free and gives you access to hundreds of articles and additional benefits. See what’s included in your free membership. See what's included in your free membership.

Already have an account? Log In